AMBREY INSIGHT>UNAUTHORISED ANCHORING IN MALAYSIA: ENFORCEMENT TIGHTENS, RISKS RISE

“For clients, the practical rule is simple: do not anchor in Malaysian waters without prior approval from the Marine Department.”

Source: This document has been approved for distribution by Ambrey Analytics Ltd.

EVENTS

On 11 October 2025, Melaka MMEA detained a foreign-registered general cargo vessel with 11 crew approximately 3.9 nautical miles southwest of Pulau Undan for anchoring without permission. Four days earlier, on 7 October, Penang MMEA detained a Panama-registered tanker northwest of Muka Head on the same grounds; reports also note non-cooperation during document checks.

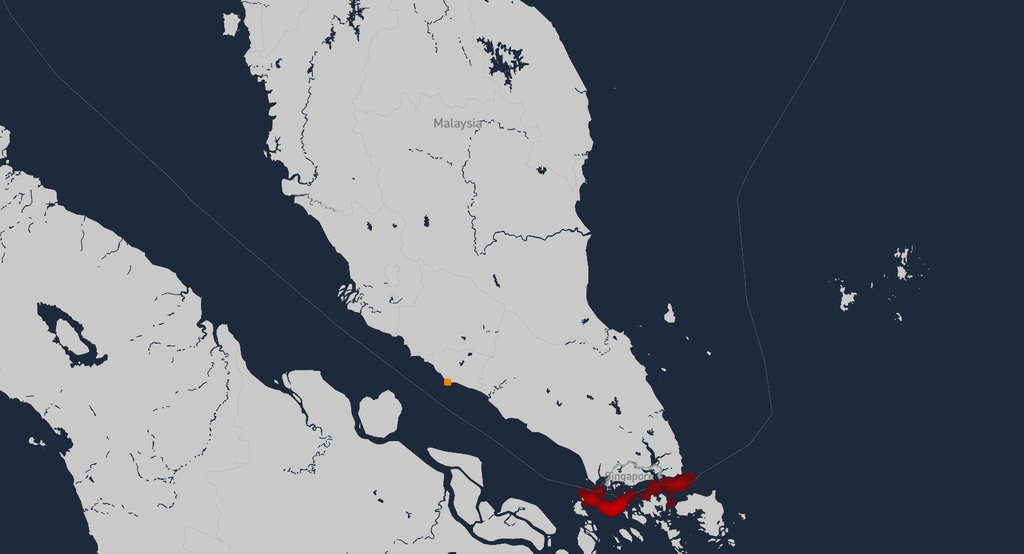

These are not isolated incidents. Since August, Malaysian authorities have conducted a string of similar detentions for anchoring without permission. On 22 August 2025, MMEA Selangor detained a barter-trade cargo ship 0.6 nautical miles southwest of Sementa after the master failed to produce an anchoring permit; the master and second engineer were taken ashore for investigation under MSO 1952 section 491B(1)(l). On 11 September, Johor MMEA stopped a landing craft tank 1.1 nautical miles southwest of Pulau Kukup for the same offence, and on 23 September detained a Panama-registered tanker 4 nautical miles west of Tanjung Piai under the same provision. Taken together, the August–October actions sit squarely within Malaysia’s ongoing campaign against unauthorised anchoring and ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in its waters. Ambrey assesses that enforcement is now systematic rather than ad hoc, with detention the default for unauthorised anchoring.

CONTEXT

In late July and early August 2025, Malaysia formalised a stricter regime for anchoring and ship-to-ship activity in its waters. Authorities closed the Tompok Utara and Eastern OPL anchorage with effect from 31 July to halt waiting and suspected informal transfers, and designated Muar anchorage later in August as the lawful venue for ship-to-ship operations and vessel services such as bunkering, tank cleaning, dislopping and maintenance, subject to Marine Department approval. The government also signalled a zero-tolerance, detain-first posture, emphasising AIS compliance, the use of designated anchorages only, and pre-arrival approvals. These measures turned a previously ambiguous operating landscape into a clear set of rules, reducing the grey areas used for loitering near the Singapore approaches.

Illegal anchoring and opportunistic ship-to-ship activity in Malaysian waters has ebbed and flowed for years. From 2024 into early 2025, industry circulars and Malaysian media recorded periodic detentions—often of masters who claimed to be outside port limits or believed they were in a waiting area. The legal hook was almost always the Merchant Shipping Ordinance 1952, particularly section 491B(1), which requires notification and approval for specified activities, and section 491C, which enables boarding, inspection and detention. By mid-2025, three dynamics converged. First, the wider sanctions and “shadow fleet” climate dominated by the US and its partners raised scrutiny on Malaysia’s waters and increased pressure on the Malaysian government to respond. As Foreign Minister Mohamad Hasan admitted, “This ship-to-ship issue has become a thorn in our side because we are often accused of practising or allowing illegal oil transfers to take place in our waters.” Second, incidents became more discreet: ships reduced overt transfer signals, yet silent loitering persisted. Third, detentions rose along the west coast—from Penang to Selangor and Johor—bringing pressure to clarify geography and process. That culminated in the late-July policy turn, in which Malaysia publicly signalled new measures to tighten control of illegal STS and loitering, including area closures and explicit operational expectations, followed by a wave of advisories and enf

ANALYSIS – From Johor Hotspot to Coast-wide Detentions after the July Policy Shift

Before July 2025, Johor remained the historical centre of boardings and detentions, but the footprint had already begun to widen. Cases in Selangor around the Sekinchan and Port Klang approaches showed that enforcement attention was extending up the west coast even before the policy shift. After the late-July and early-August measures, the pattern broadened further to include Penang on 7 October and Melaka on 11 October. This expansion reflects two forces: displacement from the closed Tompok Utara and Eastern OPL into other west-coast waiting boxes, and a harmonised, nationwide detain-first posture across state MMEA zones.

The practical effect is clear. Whether in Johor, Selangor, Melaka or Penang, vessels that loiter or anchor without prior approval now face a predictably higher chance of boarding and detention, making what began as a Johor-centred problem a coast-wide enforcement pattern.

Following this shift, the key distinction is between law and practice. The MSO 1952 has long enabled approvals and detention. While July and August did not change the statute, they reset how it is applied. Malaysia shut Tompok Utara to waiting and ship-to-ship activity, named Muar as the lawful alternative with prior approval, and signalled near-zero tolerance for non-compliance. What some masters once treated as a grey waiting option now attracts predictable detention.

This also explains the official wording. Public releases typically cite anchoring without permission because it is quicker to establish through position in Malaysian waters and the absence of an approval letter. Suspected transfers can still be investigated through cargo and equipment evidence, but the anchoring offence alone is sufficient to board, detain and pursue enquiries, and will likely remain the primary public charge even when transfer risk is the underlying concern.

The closure and the tighter procedures have reshaped the behaviour of operators and masters within Malaysian waters. Instead of proceeding to designated anchorages with approvals, some vessels—often under charterer pressure—have adopted short-term box-waiting inside jurisdiction and slow-speed loitering just outside port limits, patterns that now draw rapid attention. These practices pre-dated the policy turn, but enforcement is faster and more consistent, as recent detentions in Selangor, Penang and Melaka show. In practical terms, Muar functions as the pressure valve for legitimate transfers and services, but only where approvals are secured in advance and anchorage conditions are followed.

There is also outward displacement. A short move into Indonesian waters around the Riau Islands does not remove risk, as Indonesia requires anchoring permits and the payment of port and anchorage charges, and has a record of detaining and prosecuting unauthorised anchoring, including cases off Batam and Bintan. Farther offshore in the South China Sea, the probability of a coastal boarding may fall, but sea-state, longer emergency response times, and satellite and AIS-based scrutiny raise safety and reputational risks. These patterns are not new and are likely to persist under the new Malaysian regime, remaining poor substitutes for compliance at designated anchorages.

IMPLICATIONS & SOLUTIONS

Day-to-day operating rules

- Treat anchoring and ship-to-ship operations as permit-controlled activities.

- Anchor only in designated areas with prior approval.

- Use Muar when a lawful stop is required and keep the approval letter ready on the bridge.

- If Muar is not workable, remain underway at safe speed and avoid drifting or anchoring in Malaysian waters while awaiting orders.

- Tighten charterparty language to remove incentives for grey-zone waiting and allow time for lawful operations at Muar.

On-board inspection pack

- Keep a readily accessible folder so the watch can produce documents without delay.

- Include: approvals, chart overlays of designated anchorages and port limits, the passage plan and waypoints, VTS records, pilotage records, day-shape checklists, lighting checklists, AIS records, and local agent contacts.

If boarded

- Cooperate and present approvals at once.

- Record all requests and actions.

- Notify the insurer and the agent.

- Escalate promptly to company management and appointed legal counsel if documents are seized or crew are asked to give statements ashore.

Alternatives outside Malaysia

- In Indonesian waters around the Riau Islands, secure permits in advance, budget for port and anchorage charges, and expect checks.

- For open-sea transfers in the South China Sea, use conservative weather windows, confirm the insurer’s positions in writing, ensure AIS compliance, and keep a clear documentary record.

Outlook and monitoring

Brief clients promptly if the risk picture changes.

Expect continued boardings through the fourth quarter as authorities consolidate the regime.

Track approval uptake at Muar, monthly detention cadence by state, any re-emergence of quiet loitering patterns, and signs of cross-border displacement.

CONTACT INFORMATION

Ambrey: +44 203 503 0320, intelligence@ambrey.com

AMBREY – For Every Seafarer, Every Vessel, Everywhere.

END OF DOCUMENT